|

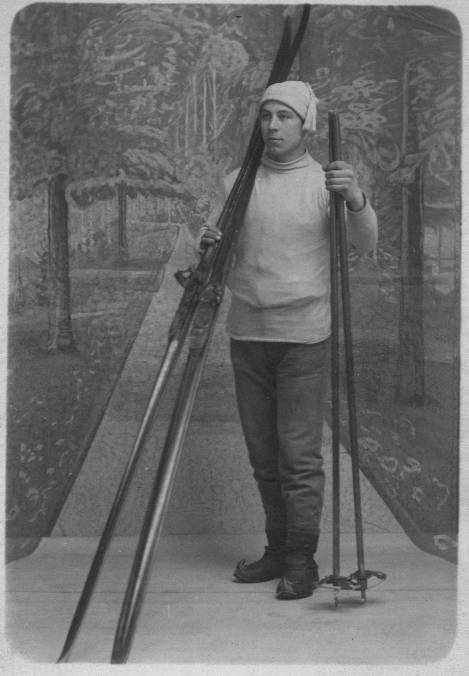

| Image 1. "New" skis versus old skis. Would the old skis manage to hold their own against more modern equipment? |

Decided to take my "new" ski poles and my old 3 meter skis on a small tour. I headed out with Patrik Berghäll, a wilderness-instructor for the Folkhälsan Association in Finland.

|

| Image 2. "Traditional" ski pole roof rack. |

We drove to Kurjerahka, a beautiful wilderness area just North of Turku. Kurjenrahaka. This area looks like most of Finland used to look like before the moors where drained for fields and forestry. We still have a lot of moors left, but approx. ½ of all the moors in Finland have been destroyed over the last 100 years.

|

| Image 3. The first time these skis have been worn for god knows how many decades. |

What also makes this area interesting is that wolves have returned to the scene. Finding wolf tracks in here is fairly common these days. We saw no wolves this time but got to enjoy some beautiful scenery and sunny skies. Clouds rolled in after midday and we found ourselves in the midst of a thick snowfall as we returned to our car.

|

| Image 4. The ski trail across the beautiful Kurjenrahka high-moor. |

We started of skiing on a frozen crust of snow and it was easy travelling as the skis kept us from piercing through the crust. I however managed to break both staves as I tried to negotiate a sharp turn on a wooden bridge that led to the ski trail. The breaks where not catastrophic as bot of the poles broke at the ends and it was the antler tips that broke of. Only one of the poles needed some additional mending during our stop at the fireplace.

| ||

| Image 5. Easy going. |

The old skis were surprisingly smooth and easy to use, even if I couldn't use my other ski stave to it´s full potential until I had a chance to mend it. I also tied a hemp cord around my heals and the skin thong bindings to prevent my foot from slipping loose. However the it was warm enough for the snow to melt on the cord and I had to re-tie the cord a couple of times during the trek.

|

| Image 6. A old "kammi" with a partially collapsed roof. |

We came across some surprises during our trek to the camp-site such as an old "kammi", a small semi-subterranean cottage used by hunters and wood cutters. We also came across an old "kota" frame in the woods.

|

| Image 7. Old kota frame. |

We made a stop for coffee, sausages and tasty pea-soup at the camp-site which happened to be fairly close to the "kammi". It started to snow as we were making our way back to the car. I had only applied tar to my skis and the sudden rise in temperature made the wet snow stick to the running surface. Luckily we only had about 1 km left to the parking when the ski tour began to feel as a real struggle.

|

| Image 8. Wet snow. |

Wet snow conditions are traditionally considered as the worst possible conditions for traditional wood skis. In Finnish this particular circumstance is called "takkala".

|

| Image 9. Heavy going, 3 cm thick snow stuck to the running surface of the skis. Feels like wearing very heavy shoes with high heals. |

I suddenly found myself thinking about my mother. She was born in 1948 in Ostrobothnia and during winter she, along with her sisters and the boys of the village, had to ski for some 3 km across a moor, fields and two forested hills to reach the elementary school in another village. She had told me about how tired and cold she used to be as she struggled to get to school during the dark hours of the morning. She had to use old worn down wooden skis. She also told me of how hard it was when it was warm and the snow clung to the bottom of the skis and travelling was almost impossible. I really felt for her as I found myself in the same situation, I however am an adult male, she was only a seven-year old girl. Life was hard. I am grateful that my seven year old daughter does not have to experience what my mother had to endure on a daily basis, I however feel that it's good for my children to learn of how life was used to be so they get a bit of perspective on their own lives.

|

| Image 10. One of my ski poles after the trip. |

Photo Credits

Image 1-10: Marcus Lepola